The Otto Foundation’s mission is to promote reading for enjoyment. We know that when children enjoy reading, they become better readers, and that this can have a significant impact on their academic achievement. Improvements in education outcomes are good news. And the fact that reading for pleasure can mitigate educational disadvantages associated with socio-economic status is great news in the South African context. In stressing the impact of reading for pleasure on education outcomes we do, however, tend to underemphasize another set of important benefits associated with “raising readers” – namely, the impact of reading on the social and emotional wellbeing of children.

The socio-emotional health of South African children is a serious concern. The 2022 South African Child Gauge published by the University of Cape Town’s Children’s Institute is a sobering read. Their research found that “South African children are exposed to extraordinarily high levels of adversity, which increases their risk of developing mental health challenges”- including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as neurodevelopmental disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autism. Mental health stressors include the fact that “two-thirds of children (63%) in South Africa live below the upper-bound poverty line, nearly one in two children (42%) have experienced violence, including physical violence (35%) and sexual abuse (35%) and in some parts of the country, almost all children have either witnessed or experienced violence in their homes, schools and/or communities”.[i]

Reading will clearly not be a cure-all for the root causes of these mental health challenges. It is, however, worth considering the potential positive impacts of reading on socio-emotional well-being that are identified in international research.

Relationships and conversations

Reading together offers physical closeness and shared attention, which aids bonding and attachment. It can help children feel secure and loved. [ii]

Adults reading and discussing a story with a child signal their emotional availability and their willingness to support the child in making sense of things that are happening around them.

Many of us can recall our own experiences of a supportive friend, teacher or librarian who gave us the right poem or story to read during a difficult period in our lives. Bibliotherapy (or “healing through books”) is described as “a strategy for librarians and teachers to help students identify, work through, and ultimately find resolution to stressful situations”.[iii]

We often see this type of interaction in our libraries – where a story would trigger a conversation around a topic that children find hard to understand and may be reluctant to bring up themselves.

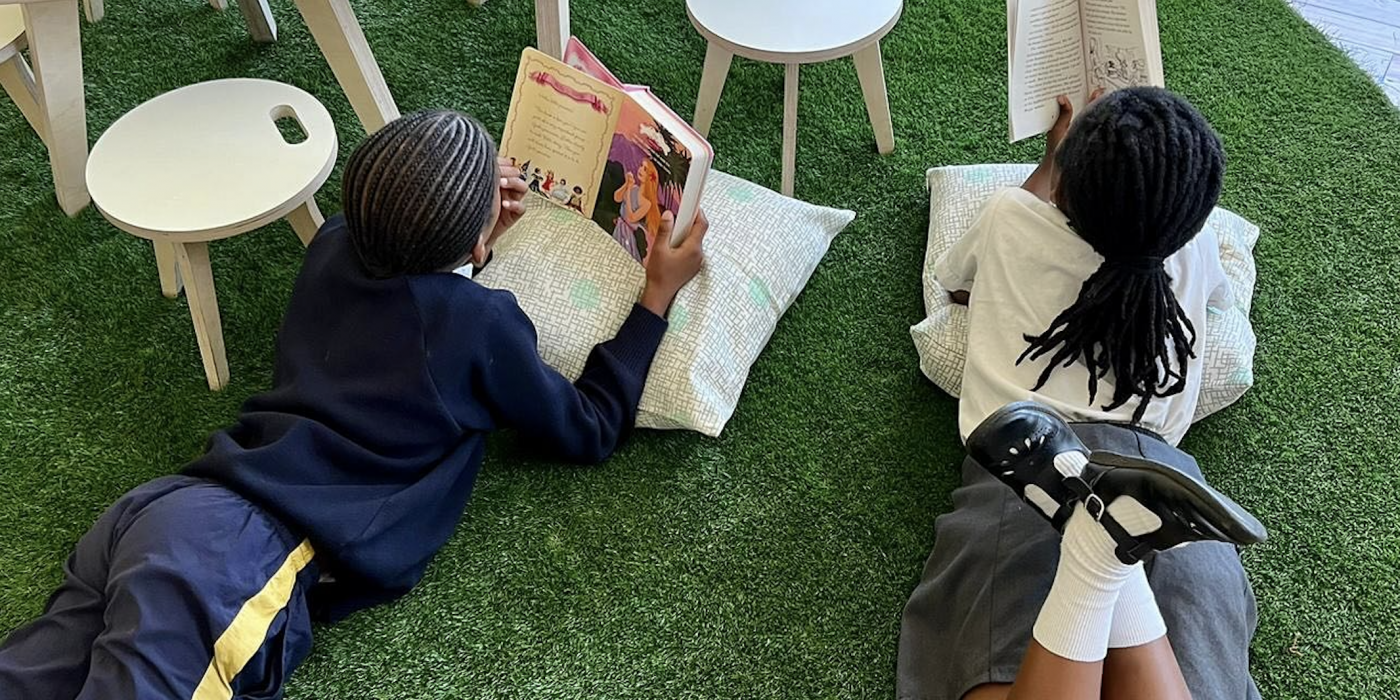

Building social bonds between children

There is a misconception that reading is a solitary activity. Successful programmes to promote reading for pleasure are, however, often developed around a variety of mechanisms to facilitate social engagement around books and stories. The Open University’s Research Unit on Reading for Pleasure calls this “book chat”, stating that “Talk is fundamental to reading and being a reader. It is the medium that allows you to articulate and share your thoughts, feelings and ideas about a text and listen to those of others”.[iv] As such, book chat can be a safe and creative way for children to develop shared interests and build social bonds.

Research also suggests that the “simulated social experience” or “reading of other minds” provided in works of fiction supports the development of empathy and interpersonal skills.[v]

In addition, in an increasingly divided world, “stories portraying cultural diversity can foster the belief that race [and other forms of difference] is not a barrier, but rather a contribution to the beauty of our multicultural world”.[vi] Recent South African picture books support this type of recognition and celebration of difference, and it is incredible to see how discussions around these books allow children in our libraries to be sincerely curious about each other, and to appreciate their own unique histories and identities.

Ability to handle diversity

In reading stories with children, and encouraging them to formulate and re-formulate potential outcomes, children practice their “mental flexibility” and problem-solving and develop an openness to new situations.[vii]

Positive impact on self-esteem

Carefully designed initiatives to promote reading for pleasure celebrate the choices, voice and creativity of children. Small things like trusting children to select their own books, engaging with children’s opinions in conversations around books and recognizing their voices as creators/ authors (letting them tell their own stories) allow them to develop positive identities associated with their status as readers and writers.[viii]

Where reading initiatives include books that are contextually relevant to the children involved, they can act both as a motivator for reluctant readers and a powerful support for identify formation – as readers see themselves and people like them celebrated and recognized in the stories they read.[ix]

Libraries as a safe space

Research on the benefits of school libraries increasingly emphasize the value of libraries as a safe space in schools. Libraries are described as “sanctuaries” and places to “regain emotional equilibrium”.[x] We certainly see this in our schools where the library is often one of few spaces in the school environment designed with the comfort and joy of children in mind, where activities tend to be quiet and calming, and where we deliberately try to tone down the level of visual overstimulation that tend to be the norm in text- and colour rich classrooms.

Given the national and international concern around the wellbeing of children, these and other socio-emotional benefits of reading are worth noting and appreciating. Our team sees these dynamics play out in our libraries every day. It is not mere theory, but viscerally experienced in our interactions with children in our library spaces. We will continue to look for ways in which the well-being of the children in our school communities can be supported through our library programmes.

[i] Tomlinson, M., Kleintjes, S. & Lake, L. 2022. South African Child Gauge 2021/2022. Cape Town: Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

[ii] Betawi, I.A. 2015. ‘What effect does story time have on toddlers’ social and motional skills’, in Early Childhood Development and Care. 185(4).

[iii] Harper, M. (2017). ‘Helping students who hurt: Care based policies and practices for the school library’, in School Libraries Worldwide, 23(1).

[iv] Open University. ‘Developing Reading for Pleasure: engaging young readers. The role of talk and book chat.’ Available. [Online]: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=126133§ion=_unit3.8

[v] Djikic, M., Oatley, K. & Moldoveanu, M. 2013. ‘Reading Other Minds: Effects of Literature on Empathy”, in Scientific Study of Literature. 3(1).

[vi] Grasso, M. ‘The Importance of multicultural literature’. Available. [Online]: https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-96/the-importance-of-multicultural-literature/

[vii] Sturm, B. 2013. ‘Bibliocreativity: how books and stories develop creativity’, in J. Jones and L. Flint (eds.) The Creative Imperative: School Librarians and Teachers Cultivating Creativity together. Santa Barbara: Liberaries Unlimited.

[viii] The Mercer’s Company. Reading and Writing for Pleasure: A Framework for Practice: Executive Summary’. London: The Mercer’s Company.

[ix] Grasso, M. ‘The Importance of multicultural literature’. Available. [Online]: https://www.scisdata.com/connections/issue-96/the-importance-of-multicultural-literature/

[x] Merga. M. 2020. ‘How Can School Libraries Support Student Wellbeing? Evidence and Implications for Further Research’ in Journal of Library Administration. 60(6).